Five reasons why Kenya's cybercrime law is being opposed

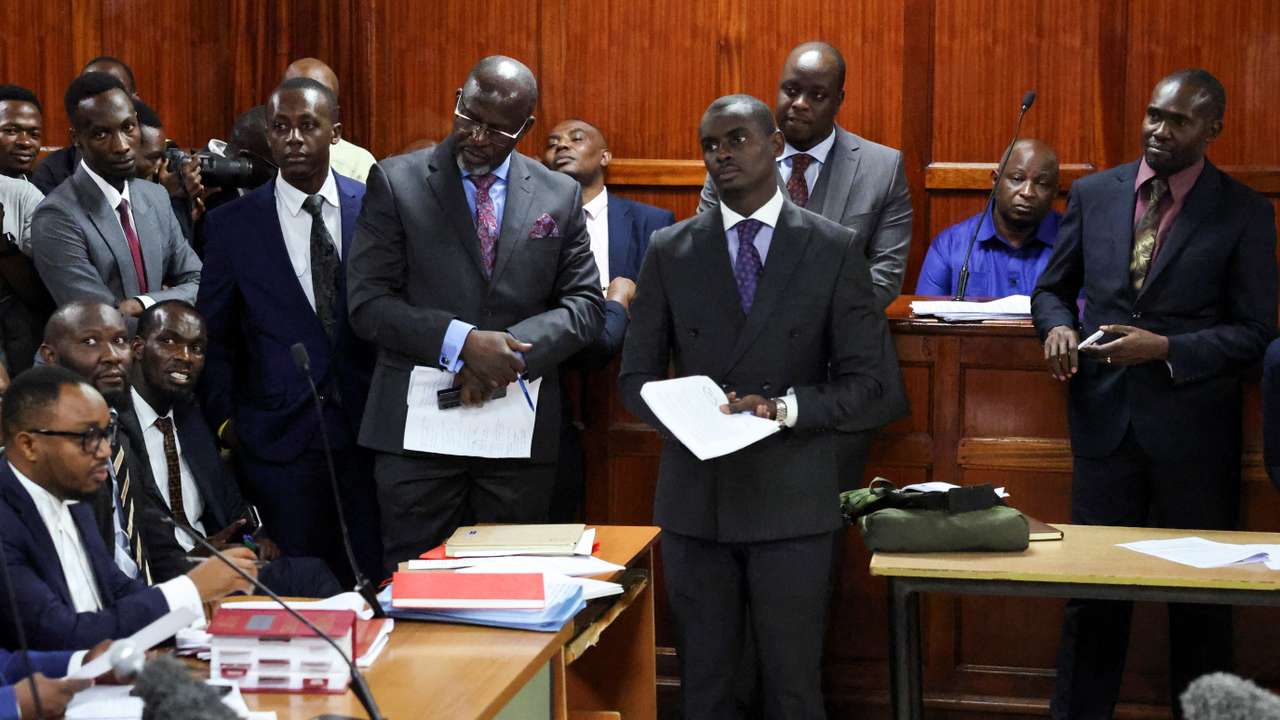

Kenyan journalists, bloggers, and lawyers are back in court, urging the Court of Appeal to strike down the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act, 2018.

The coalition, led by the Bloggers Association of Kenya (BAKE), the Law Society of Kenya (LSK), and the Kenya Union of Journalists (KUJ), has argued that the law has been weaponised to silence dissent, intimidate critics, and undermine constitutional freedoms, the Nation.Africa reports.

Here are five of their main objections:

1. Suppression of free speech and dissent

The coalition says the law has been used less for cybersecurity and more as a political weapon. They cited cases of bloggers arrested for “fake news,” an author detained for writing a presidential biography, and a developer targeted for building a Finance Bill monitoring tool.

According to BAKE lawyer Mercy Mutemi, the law was a “panic response” to online dissent, not a genuine attempt to tackle cybercrime.

2. Abuse leading to harassment and even death

Perhaps the most shocking example is the case of teacher Albert Ojwang, who reportedly died in police custody after being arrested over a social media post.

Lawyers argued the Act gives police sweeping surveillance powers, leading to harassment, abductions, and abuses that endanger lives.

3. Violation of constitutional rights

The coalition members claim the law infringes on freedoms of expression, privacy, and judicial independence. Section 50, for example, requires courts to automatically grant police access to digital data if “reasonable grounds” are claimed, a provision Mutemi said turns courts into “rubber stamps” instead of independent watchdogs.

4. Lack of public participation

Another key objection is procedural; significant amendments adding new “content offences” were introduced at the committee stage in Parliament without public consultation. Critics have therefore argued that this violates Kenya’s constitutional requirement for public participation in lawmaking, making the Act illegitimate.

5. Less restrictive alternatives exist

Lawyers insist that there are civil remedies, such as defamation suits, that can protect reputations without criminalising speech. As lawyer Dudley Ochiel argued, criminal provisions like those targeting false publications or cyber harassment are overly broad and open to abuse. Civil law, they say, would strike a better balance between protecting reputations and safeguarding free expression.

The state, represented by the Attorney-General, the DPP, and Parliament, has urged the court to uphold a 2020 High Court ruling that declared the law constitutional, insisting that regulating digital activity is necessary in the age of technology. The ruling is set to be delivered in February 2026.

This story is written and edited by the Global South World team, you can contact us here.